Program Notes: When Time from Time shall Set Us Free

The Genre of Art Song and Schumann’s Liederkreis (1840)

Robert Schumann

The joy of art song is, yes of course, in the beauty of the music, but it is especially in the interaction of music and poetry. Last year I saw the film A Complete Unknown and it featured some nice excerpts of Bob Dylan’s classic sixties songs, plus some Joan Baez and others. It struck me that Dylan and Baez were really torchbearers of the art-song genre, since so much of their output is “poetry set to music.” Of course one could argue that all song lyrics are poetry, but I’ll make a slight case for a distinction here on the basis of how “heightened” or “artsy” or “abstract” the lyrics may be. In Dylan’s case, it often feels like the music is in service to something unusually serious and cerebral in the poetry. Another group that gives me this feeling is the Grateful Dead, when they are playing songs on lyrics by the ever-imagistic and mood-building Robert Hunter. Lots of others could fit this bill, too, and I’m certainly not here to argue against any songwriter for inclusion in this lineage. My point is just to highlight this concept: poetry set to music. Not just a catchy lyric to go with a catchy tune, not just a single straightahead sentiment (like “please be mine,” “I love you,” or “I’m sad you’re not mine”), but something more ethereal and complex. This is the gift, too, of art song.

Robert Schumann is one of the big daddies of all art-song composers, writing classics such as his Dichterliebe (“a poet’s love”) and Liederkreis (“song cycle”), Op. 24, both on poetry by the German Romantic poet Heinrich Heine, and the cycle Victoria and I will be presenting on 2/16, Liederkreis, Op. 39, on poetry by another German romantic poet, Joseph von Eichendorff. I have really been enjoying getting into the poetry of Liederkreis, Op. 39, also sometimes called the “Eichendorff Liederkreis” to distinguish it from the Heine Liederkreis.

The title Liederkreis translates, ever so simply, to “Song (Lieder)-round (Kreis)” or “Song-cycle.” The art-song tradition in Western Art Music finds some of its most exceptional exponents in the German genre of the Lied, about which the music critic Jon W. Finson writes (again pointing to the art song’s form as poetry-set-to-music),

We must always understand that the Lied is a literary experience as much as a musical one, and we can translate the word itself either as “lyric” or “song.” In fact, during Schuman’s day, poets regularly gave public readings of their Lieder before literary societies as well as releasing them in print.

Jon W. Finson calls the Eichendorff Liederkreis part of “the long tradition of ‘Wanderer’ cycles documenting a young man’s adventures in the wide world.” This certainly seems to be a through-line in the cycle, of which two different songs (#1 and #8) are titled “In der Fremde,” or “in a foreign land,” and another (#6) is titled “Schöne Fremde,” or “a beautiful foreign land.” In the opening song, one of the two titled “In a Foreign Land,” the poet speaks of being far from home, casting his thoughts back “beyond the red lightning,” to his distant homeland:

From my homeland, beyond the red lightning,

The clouds come drifting in,

But father and mother have long been dead,

Now no one knows me there.

How soon, ah! how soon till that quiet time

When I too shall rest

Beneath the sweet murmur of lonely woods,

And no one knows me here either.

It’s important to know that, although the words of each poem are by Eichendorff, the wanderer’s overall journey is really the work of Schumann: it was Schumann who chose and ordered the twelve songs of the Liederkreis out of the many candidates in Eichendorff’s collection Intermezzo. The wanderer’s journey is not a straightforward one (nor would we wish it to be!), with many of the movements being static meditations on forlorn love—though not so stormy and melancholic as the failed-love story in Schumann’s Dichterliebe—and some being being scenes of fantasy, like the knight in song 7, who has slept for centuries in a high tower until his “hair and beard are grown together, and his breast and his collar-ruff have turned to stone.”

Overall, the Liederkreis songs feel more reserved and compact than those of Dichterliebe. Eichendorff’s verse forms are less adventurous than those of Heine. Eichendorff almost always writes in quatrains, strongly favoring an alternating rhyming scheme, and almost always in lines of three or four feet. Thus, the songs of Liederkreis, Op. 39 end up feeling like charming miniatures.

Although our recital, as many in the last 160 years, will present these songs in a concert format, as performed by two professional performers, it may help our appreciation of these poetic miniatures to remember that (again quoting Jon W. Finson):

Musical Lieder, whether published in cycles or miscellaneous collections, formed one of the many varieties of Hausmusik—compositions made primarily for talented amateurs to perform at home. One or two Lieder might occasionally appear on a concert program (along with a scattering of opera arias, individual pieces of chamber music, and then, if an orchestra was available, a symphony). But Germans during Schumann’s day never considered Lieder the province of professional singers and musicians, let alone appropriate in a public setting devoted entirely to them. The Liederabend (a professional chamber-music concert devoted solely to songs) as we know it today did not make its appearance until the 1860s.

It is curious to think, however, of amateur pianists tackling Schumann’s intricate and sometimes finger-tying accompaniments. We will be blessed to have ours played by the masterful Victoria Kirsch, about whose biography you can read more at the bottom of this post! Schumann’s piano parts always do more than merely accompany the singer, or provide a scaffolding for the vocalist’s melody: they are always integrally expressive of the meaning of the songs, and at times provide ironic contrast or commentary on the meaning of the lyrics. As an example of the expressive power of the accompaniments, consider the beautiful introduction and accompaniment to song #5, “Mondnacht,” in which the piano’s descending, harmonically-melting figures evoke the moonlight dripping down upon the pastoral scene in which the poet is immersed. About this unique song, Finson writes:

Schumann’s setting suspends all sense of motion for the first two stanzas of the poem through a series of incessantly repeated notes in the piano, a constant repetition of a single melodic phrase for each couplet, and a lack of clarity about the centering key.[...When the poet’s] soul leaves his body [in the final stanza] and flies over the landscape “as if flying home,” Schumann underlines this uncanny experience, expanding the melodic range (“spread[ing] wide its wings”) and finally confirming the actual key to bring the setting “home” (“nach Haus”). Many critics consider this song the most perfect and beautiful combination of text, melody, and instrumental writing in the history of the German Lied.

For attendees at our February 16th concert, Victoria will be reading the translations of each song aloud, because the interaction between the poetry and the music is so profound and lovely. Of course, simply sitting and enjoying the beautiful sounds is always a valid option as well.

Because we believe Schumann’s work to be a point of reference for the later composers we present on our “Liederabend,” Victoria and I will be taking the unusual step of using the Liederkreis, Op. 39 as a “frame” for the rest of our recital: we will divide the 12-song set into three groupings of four, which we will present before, between, and after the other three song-cycles on our program. Thus, Liederkreis will appear as the “background” against which our offerings of Ravel and Carlson are set.

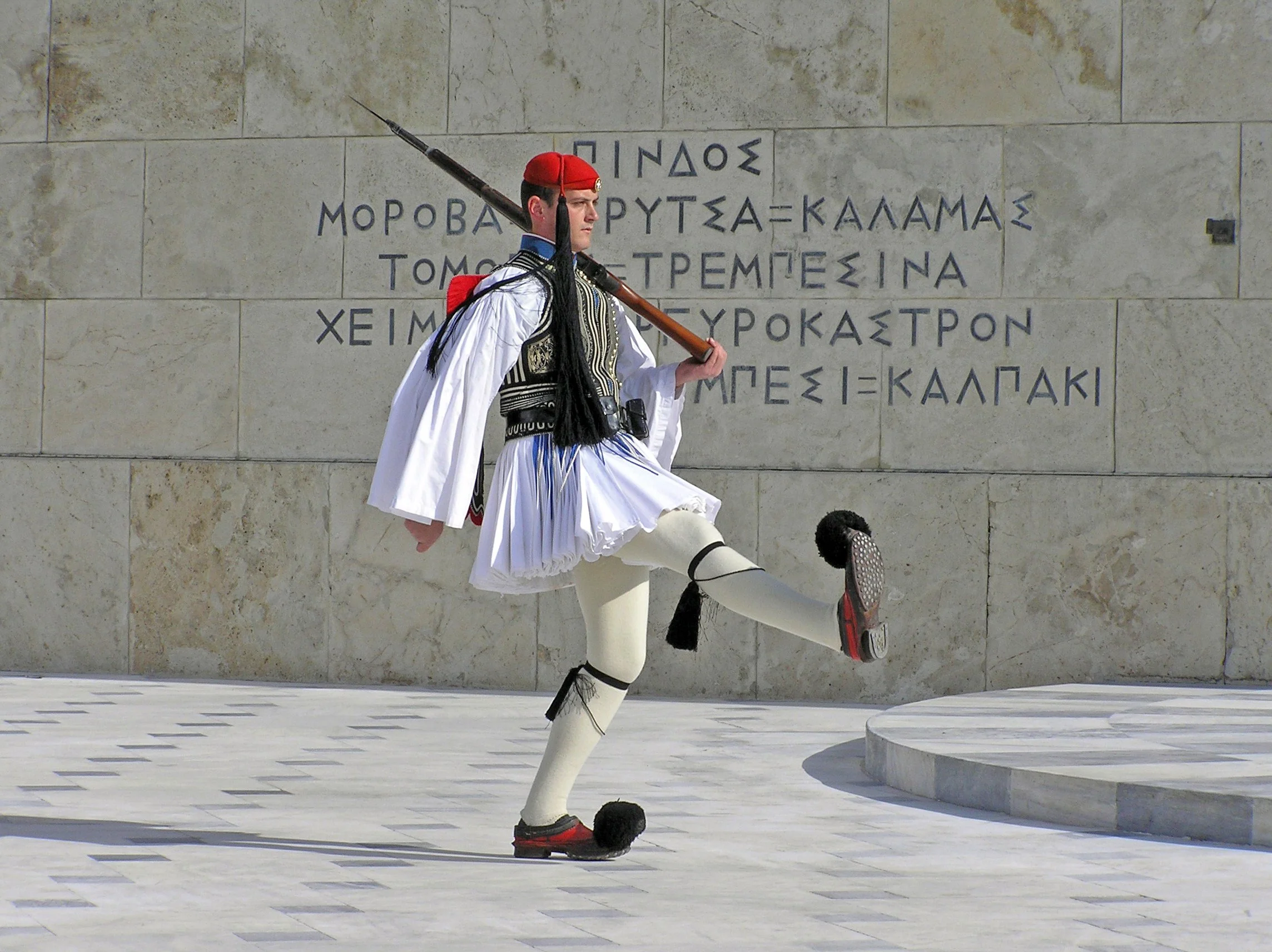

Finding the Fine in the Folk: Ravel’s 5 Greek Popular Songs (1904)

Above, I mentioned the inimitable Bob Dylan—and the biopic A Complete Unknown. I was relating Bob’s work to the genre of the art song overall, both of which can be described as “poetry set to music.” As I sit down to write a little meditation of Ravel’s 5 Popular Greek Melodies, I once again have A Complete Unknown in mind.

I’m thinking of that wonderful phenomenon called FOLK MUSIC. In A Complete Unknown, we are plunged into the U.S. folk scene of the early- to mid-sixties. Here we meet towering figures like Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie—musicians who believed not only in the authenticity of their folk singing, but also in its capacity for social influence.

I find folk music so wonderful and interesting…what sort of music arises spontaneously from populations who are neither conservatory-trained nor paid for their musical efforts? It is a favorite fact of mine that every single human culture produces music—one could argue, even, that music is somehow a biological trait of the human animal! I’ve always delighted in folk music of various cultures because to me it speaks very poignantly of nothing less than what it means to be human. Of course, a culture’s folk music will end up reflecting the important aspects of everyday life for them…agricultural societies will have field songs, warrior cultures will have battle hymns, and so on and so on.

The genre of music called “Folk” in your local record store, of course, does not compass all the world’s folk music traditions…but of course it is the record store’s British-American folk that we’re made to think of in A Complete Unknown, and in another great movie I rewatched recently, the Coen Brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis. Still, the premise remains: this is the music that comes from the people, from the workers, the villagers, the homemakers, rather than from the conservatory-trained elites.

There is a wonderful scene depicting an encounter between the two types of musician in Inside Llewyn Davis; Davis, a folksinger, attends a dinner party with his friends who are on faculty at Columbia, and is introduced to a couple musicians from “Musica Anticha,” a Baroque group. Trying to relate, Davis asks if they know his childhood piano teacher, Mrs. Siegelstein. A bit flummoxed by the question, the Baroque keyboardist can only cordially ask, “uh, does she play Early Music?”

In our recital, the encounter of the folk with the refined is much more fertile, and less awkward. The Greek songs that Ravel orchestrates as his 5 mélodies populaires grècques (5 Popular Greek Melodies, or more idiomatically translated, 5 Greek Folk Songs) are earthy, full of life, and yet at times quite exquisitely delicate, and even unexpectedly complex. The first song, “The Awakening of the Bride,” is jocular and excited, the second, “Yonder by the church,” is solemn and mournful. The third, “What gallant is my equal?,” is masculine and braggadocious, while the fourth, “Song of the mastic-harvesters,” is pensive, lyrical, and meandering. The cycle is capped by “All merry!,” a rambunctious dance with plenty of rhythmic “laralarala’s.”

This cycle cannot even properly be said to be “by” Ravel, though popular usage names him the composer. In reality, he is the arranger, or even more accurately, the orchestrator, of melodic materials he did not invent. This cycle is a marriage of the folk and the conservatory—Ravel’s accompaniments are slick, urbane, and musically modern. Yet they also elevate and highlight the inherent characters of the folk melodies; they neither erase nor overshadow the beauty and vitality of the respective folk songs. This meeting of the folk and the “classical” is much more productive than the one Llewyn Davis experiences in that uptown apartment.

Singing these songs in Greek greatly enhances the feeling of authenticity for me. These five songs were set by Ravel in French translation. Sung in French, they sound hopelessly urbane, thanks to French’s languorous nasals and endless vowel sounds. The Greek lyrics have been a delight for me to study…Greek has sonorous consonants separated by pure vowels, like the vowels of Italian or Spanish. It sounds both stately and earthy, both high and low, both ancient and timeless. I truly believe everyone will enjoy hearing these songs in the original Greek!

In the overall flow of this recital, I can only appreciate the note of folkish vitality that these songs introduce, a counterbalance to the weighty German Romanticism of Eichendorff, and to the cerebral Modernism of cummings. Come and hear!

A Conversation with the Composer: Mark Carlson’s This is the Garden (1987)

The last cycle I am going to highlight for our program is a fantastic three-song set by a living composer, and my friend, Dr. Mark Carlson. Carlson’s This is the Garden sets three poems by the ever-exuberant E.E. Cummings (Mark advises me that capitalizing all three initials is correct, although I am still very attracted to the lowercase styling, e.e. cummings, which was used in publishing and criticism for so much of the twentieth century…something about it suits the whimsy and earthiness I associate with Cummings’ work). Instead of another meditation from me (and since, unlike Schumann and Ravel, Carlson still lives and breathes) I thought it would be a special treat to do this program note in the form of an interview with the composer. Please enjoy this back-and-forth on Mark’s extraordinary career, and what listeners can expect to experience on Presidents Day:

—————

JB: Can you talk about your relationship to the genre of art song?

Composer Mark Carlson

MC: I have always loved songs, in general, and loved singing—alas, without the benefit of a good voice. My family sang together quite often, and especially loved folk songs and the songs of the folk movement of the 1960s. I also loved the songs of what is now called “The Great American Songbook,” though I took them for granted for a long, long time. I dipped my toe in the water of classical music songs during college, but I really didn’t discover the wealth of these songs until I moved to LA in 1974, after graduating from California State University, Fresno. My mentor, Alden Ashforth, was fairly obsessed with songs, and he immediately started inundating my ears and my brain with songs of Schubert, Schumann, Schoenberg (The Book of the Hanging Garden was a favorite of mine at the time), among many others, including Debussy, Ravel, and Fauré. Alden was very particular about how words are set—both in terms of rhythm and meaning—and that has stuck with me ever since. I wrote my first good song in 1975—a song I still love; it was the final song of my first song cycle, Patchen Songs, eight songs on poems by Kennet Patchen. I took voice lessons for a couple of years in my late 20s, ostensibly just for fun, but also so that I would have a better sense of how to write for voice. I LOVE poetry, and love setting appropriate poems to music. I have now written more than 60 songs, and I intend to keep writing songs as long as I am able.

JB: How would you describe your compositional style to those who are wondering what to expect?

MC: That’s always a hard question to answer, as it always feels limiting. My best answer is that my music is always melody-oriented (flute—a melodic instrument, if ever there was one—was my main instrument, which I played professionally for most of my life), lyrical, overtly emotional, largely tonal, and stylistically eclectic.

JB: I love the poetry of these songs; in fact, a line from the second song, “when time from time shall set us free,” became my choice for the title of this entire recital! What led you to these poems by E.E. Cummings?

Cummings

MC: When I was teaching my first undergraduate composition class at UCLA in 1986-87, I assigned the students to each write a song to an existing poem, and I had them bring in poems of their own choosing. One student chose a Cummings poem, if there are any heavens, which I had not previously read. I was stunned by its beauty and was intensely moved. As soon as I could, I went down to the campus bookstore (remember those?!)—which had an amazing selection of poetry—and bought a volume of his Complete Poems. I was in love, and I pored over those poems for a long, long time. It so happened that I was soon to write songs for a concert on the first full season of my chamber music series Pacific Serenades, and I chose three Cummings poems for that project; it is these songs which Justin and Vicki will be performing on their upcoming program.

JB: What should listeners listen out for in your cycle?

MC: It’s all about the words!

JB: Do you feel this cycle, or your songs in general, have any affinity with the other composers & cycles on this program—Schumann Liederkreis, Op. 39, and Ravel 5 Greek Popular Melodies?

This is the garden.

MC: Yes! Among the most influential music on me as a composer are the Schumann cycles, Dichterliebe and Liederkreis, Op. 39, and perhaps oddly, Ravel’s Chansons Madécasses—for voice, flute, cello, and piano—which I performed as an undergraduate. All of those not only influenced how I treat text in writing songs, but really made me think a lot about the textures of the piano parts—and of the ensemble, in songs that are for other/additional instruments. I do not know the Five Greek Popular Melodies well enough to comment on any connection there. But Ravel is among my favorite 20th century composers.

JB: In another correspondence, you told me, "[The three songs together] have a shape, an arc, to them that is part of the essence of the songs." We have three songs here on three Cummings poems: 'The Moon is Hiding in her Hair,' 'In Time Of...,' and 'This is the Garden.' Could you say something about the overall arc of the three-song set, or the journey on which you believe these three poems bring the listener?

MC: Though it is a short set, being only three songs long, I do believe that it takes us on a journey about beauty—natural, spiritual, and artistic beauty—and about our relationship to it. It opens with a crystalline expression of wonder at earthly beauty. From there, an exuberant series of lessons for us to learn from various flowers while we are here on earth—and a glimpse into the essence of what really matters. And finally, a return to awe, this time at profound otherworldly beauty in the guise of a garden so beautiful that even Death and Time are awestruck.

About the Performers

Baritone Justin Birchell was recently seen with Anchorage Opera as Betto in Gianni Schicchi, Mr. Gobineau in The Medium, and Jake Wallace in La Fanciulla del West. Other recent engagements include singing the title role in Gianni Schicchi with Tacoma Opera, a production that also marked Birchell’s stage-directing debut, and Zuniga in Carmen, also with Tacoma. He has also recently sung The King in Cendrillon with Vashon Opera, and the Dragon and Gaffer Gubbins in The Dragon of Wantley with Anchorage Festival of Music. Recent concert engagements include singing the “Toréador” aria to a packed house of schoolchildren with the Auburn Symphony, Mozart’s Requiem with Harmonia Seattle Orchestra and Chorus, Bach’s Magnificat with University of Washington Choirs, and The Fence in Considering Matthew Shepard with Choral Arts Northwest. Notable opera roles include Faninal in Der Rosenkavalier (Pacific Northwest Opera), Dr. Falke and Herr Frank in Die Fledermaus, Silvio in I Pagliacci, and creating the roles of Manfred in Janice Hamer’s Lost Childhood and Padre Antonio in Carla Lucero’s Juana, both world premieres. Justin was a 2020 winner of UCLA Philharmonia’s All-Stars Concerto Competition and a 2018 recipient of Anchorage Festival of Music’s Ted Stevens Young Alaskan Artist Award. Birchell holds a Master's in Voice Performance from UCLA’s Herb Alpert School of Music. He also remains active as a composer, choir director, ensemble singer, and educator. Birchell’s original film score, based on his long study and admiration of the choral traditions of the Republic of Georgia (Saqartvelo), will soon be heard in the documentary Two Steps Back: Georgia’s Uncertain Future. As a choral director, Birchell was a co-winner of the 2025 American Prize in Choral Performance, for his performance of Reena Esmail’s “The Unexpected Early Hour” with the University of Washington Chorale. Birchell has been engaged as a pre-concert lecturer by the Seattle Symphony, and as season lecturer by Tacoma Opera. Birchell holds a Doctorate of Musical Arts from the University of Washington, where he studied and taught choral conducting.

Victoria Kirsch is a Southern California-based collaborative pianist and vocal coach known for creating and performing innovative programs, including concerts based on museum exhibitions and staged art song/poetry programs. She is delighted to share the stage with her former student and now dear friend, baritone Justin Birchell.

Victoria served as the onstage pianist for a wide variety of theatrical programs with soprano Julia Migenes (Carmen in the award-winning opera film directed by Francesco Rosi), touring the world for many years with the celebrated singing actress (Diva on the Verge, Schubert, Migenes Sings Bernstein, La Vie en Rose).

She has worked with national and regional opera companies, including LA Opera, serving as a member of the music staff and as a teaching artist for LA Opera’s Community Programs Department, presenting over 35 programs to educators and students.

She has served as an official pianist for the Operalia Competition and the Metropolitan Opera’s National Council Auditions, among others.

In 2008 Victoria received a Chairman’s Grant from then-NEA Chair Dana Gioia to support the co-creation of the musical-theatrical piece, Emily Dickinson: This, and My Heart, which premiered at Grand Performances in downtown Los Angeles in September 2009 with actress Linda Kelsey and soprano/stage director Anne Marie Ketchum.

Between 2007 and 2016 Victoria curated and performed twelve music/spoken word programs linked to exhibitions at the USC Fisher Museum of Art, as part of the campus’ renowned Visions and Voices program. She has also created exhibition–inspired programs for the Huntington Library and Gardens, the Getty Museum, the Robert and Frances Fullerton Museum of Art at CSU San Bernardino, and the Long Beach Museum of Art.

Since Fall 2015 Victoria has been a faculty vocal and opera coach at UCLA’s Herb Alpert School of Music, where she is now a Continuing Lecturer. In addition to her continuing faculty position at UCLA, Victoria returned to the USC Thornton School of Music in Fall 2024, this time as a member of the Keyboard faculty, working with pianists in the Keyboard Collaborative Arts department. She was previously a member of the Vocal faculty at the Thornton School (1995-1999).

Victoria was the music director of OperaArts, a Coachella Valley-based vocal performance organization; a faculty member at the Angels Vocal Art and SongFest summer programs; She was associated with the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara for many years, playing in the studio of renowned baritone and master teacher Martial Singher and serving as a member of the vocal faculty.